When you bite into a chili pepper and feel that fiery heat, you’re experiencing one of nature’s most fascinating chemical reactions. The sensation isn’t a flavor—it’s a biological response triggered by a compound called capsaicin, found naturally in chili peppers.

Understanding how capsaicin works helps explain why some spices make food pleasantly warm while others bring intense, mouth-tingling heat. From mild paprika to fiery habaneros, every pepper has its own heat profile—and it all comes down to science.

What Is Capsaicin?

Capsaicin is a naturally occurring chemical compound found in the Capsicum family of plants, which includes chili peppers. It’s concentrated mostly in the white membranes and seeds of the pepper, not in the flesh itself.

Capsaicin is odorless and flavorless, but when it comes in contact with your mouth’s sensory receptors—specifically TRPV1 receptors, which normally detect heat and pain—it creates the illusion of burning.

That’s why spicy food can make your mouth feel hot, even though the temperature hasn’t changed.

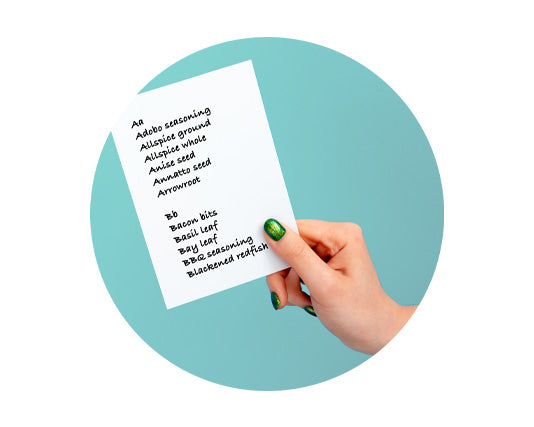

The Scoville Scale: Measuring Heat

The Scoville Heat Scale measures the capsaicin concentration in chili peppers. It was created by Wilbur Scoville in 1912 to quantify pepper spiciness in “Scoville Heat Units” (SHU).

Here’s a quick overview of common peppers and their heat levels:

-

Bell Pepper: 0 SHU (no heat)

-

Jalapeño: 2,500–8,000 SHU

-

Cayenne Pepper: 30,000–50,000 SHU

-

Thai Chili: 50,000–100,000 SHU

-

Habanero: 100,000–350,000 SHU

-

Carolina Reaper: Over 2,000,000 SHU

This variation depends on the pepper’s genetics, growing conditions, and maturity level.

Why Do People Enjoy Spicy Food?

Capsaicin triggers the same nerve receptors that respond to physical heat or pain. When your body senses this “burn,” it releases endorphins and dopamine, chemicals that create a pleasurable, euphoric feeling.

This is why many people describe eating spicy food as both painful and addictive—it literally makes your brain feel rewarded for the experience.

How Spices Create Heat and Flavor

Not all spice “heat” comes from capsaicin. Other spices and compounds create unique sensations:

-

Black Pepper (Piperine): Causes a sharp, dry heat that lingers.

-

Mustard and Horseradish (Allyl Isothiocyanate): Create a quick, nose-tingling burn.

-

Ginger (Gingerol): Produces a warm, aromatic sensation without intense heat.

-

Cinnamon and Clove (Eugenol): Deliver gentle warmth and sweetness.

Each compound interacts differently with your taste receptors, which is why “heat” can feel so varied across different cuisines.

Balancing Heat in Cooking

Managing spiciness is about creating balance, not overpowering heat. Here are a few tips:

-

Control the source: Remove seeds and membranes from peppers to reduce heat.

-

Pair with cool ingredients: Dairy, coconut milk, or avocado can mellow spice intensity.

-

Use sweetness or acidity: Honey, sugar, or citrus helps balance capsaicin’s burn.

-

Blend spice levels: Combine mild spices like paprika or cumin with hotter ones for layered flavor.

-

Taste as you go: Heat builds gradually, so add chili or pepper slowly during cooking.

The Role of Spices in Global Heat Preferences

Spice tolerance often reflects regional climate and culture. In warmer areas like South Asia, Mexico, and parts of Africa, spicy food is a staple. The heat encourages sweating, which cools the body naturally.

Over time, these culinary traditions became part of cultural identity, shaping regional spice blends—from Indian curry powders to African chili pastes and Latin American salsas.

Frequently Asked Questions About Capsaicin and Spice Heat

1. What exactly causes the burning feeling from spicy food?

The compound capsaicin binds to nerve receptors in your mouth that sense heat, making your brain think you’re feeling actual warmth or pain.

2. Why do some people tolerate spicy food better than others?

Regular exposure to capsaicin can desensitize your nerve receptors over time, meaning your body adjusts and perceives less heat.

3. How can I reduce the burn from spicy food?

Drink milk or eat yogurt—dairy contains casein, which helps break down capsaicin’s oily structure. Water alone doesn’t help because capsaicin isn’t water-soluble.

4. Do all spices contain capsaicin?

No. Only chili peppers from the Capsicum family contain capsaicin. Other spices, like black pepper or mustard, use different compounds to produce heat.

5. Does cooking affect spice heat?

Yes. Prolonged cooking can reduce capsaicin’s potency, while roasting or frying peppers can intensify it by releasing oils.

6. Why do some people sweat or cry when eating spicy food?

Your body reacts to capsaicin as if it’s real heat, activating sweat glands and tear ducts to help cool and protect itself.

Final Thoughts

Spice heat isn’t just a matter of taste—it’s a fascinating interaction between chemistry and biology. Capsaicin gives food an edge that’s both stimulating and satisfying, adding excitement to cuisines around the world. By understanding how it works, you can better control spice levels and create dishes that balance flavor, warmth, and enjoyment.